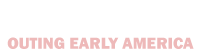

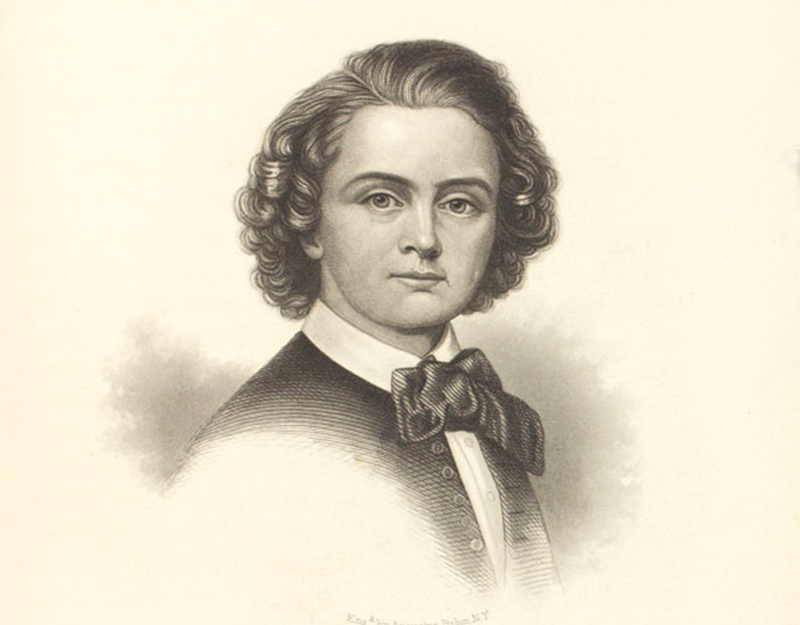

Walt Whitman. Leaves of Grass. Brooklyn, 1855.

How did readers "read" the portrait of the poet Walt Whitman (1819-1892) when it appeared as the frontispiece to the first edition of his Leaves of Grass (1855)? The jaunty image of Whitman as a young man in work clothes, with his shirt unbuttoned at the neck, would have seemed extremely casual. The book, which Whitman issued in six editions during his lifetime, celebrated living life fully, and Whitman's use of language – in his famously difficult, but casual writing – continues to challenge readers today.